In The Secret History power wears wire-rimmed glasses and speaks in conditional verbs. It often whispers in ancient tongues, cloaked in composure and rationality. Through Henry, Tartt exposes our vulnerability to quiet dominance, the kind that doesn’t demand submission but elicits it. Today we find ourselves unmoored from certainties, this longing for meaning makes us susceptible to the allure of the tragic, the beautiful, and the terrifyingly assured.

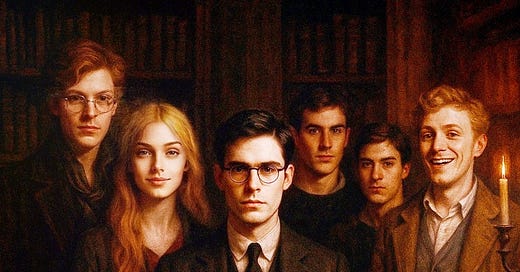

Donna Tartt’s The Secret History gathers a coterie of academically inclined eccentrics under the moody mentorship of Julian Morrow. At first glance, they appear as near-equals—bound by Greek, Latin, candlelit study, and esoteric exchange. Look closer, though, and one figure stands unmistakably above the rest: Henry, magnetic, poised, and quietly forceful. Critics sometimes point out that the other characters barely stir unless Henry moves them, but that observation underscores a deeper truth: many of us assume we’re the protagonists of our own stories, yet only a select few truly possess the gravitas to draw others into orbit. Henry wields that authority calmly, rationally and with a detachment that can feel otherworldly.

A Quiet Puppeteer

Nothing about Henry’s influence is perfunctory. He rarely issues directives; he sets an atmosphere. He orchestrates the Bacchanal and rationalizes Bunny’s murder with a composure so unyielding it feels carved from stone. His aloof air, steeped in ancient languages, endows him with a subtle hush that lures people in. Not because he demands their attention, but because he doesn’t seem to need it. Paradoxically, that refusal to solicit devotion only tightens his hold.

I’m drawn to Henry’s glacial logic. There’s a part of me that admires his willingness to cut through dithering morality. He is the personification of the iron fist in a velvet glove. Yet I also catch a whiff of arrogance in the efficiency with which he “solves” problems. That tension between practicality and hubris charges his presence with both admiration and unease.

The Exigency of Killing Bunny

Nothing displays Henry’s authority more clearly than the group’s decision to kill Bunny. Bunny’s loose tongue endangers them all, and Henry frames murder as the only remedy. It’s not out of vindictiveness he chooses this path, but logic. A cold, measured step resulting in an appalling in flagrante delicto that taints their once-cohesive circle. He does so with aplomb—like a farmer calmly dispatching lagomorphs from his fields.

Richard, our narrator, follows Henry’s lead almost by reflex, as though calm automatically equates to correctness. The others comply with a nearly mechanical submission, each incremental horror feeling more ipso facto than deeply believed. On one hand, I see Henry’s point: Bunny really does threaten their world. On the other, I recoil at how neatly Henry reduces a life to an inconvenient obstacle to be removed.

Bunny vs. Henry

Bunny, for his part, tries to play the charming ringleader, but his showy humor never lands with true weight. Faced with Henry’s steady confidence, he seems a hollow lusus naturae—an imitation leader lacking real gravity. Yet it’s more than mimicry; it’s mythic friction. Henry is the Apollonian principle: restraint, clarity, the cold logic of form. Bunny is Dionysian: unruly, theatrical, absurd—but also necessary. His presence disturbs the group’s fragile order, but it also injects it with vitality. He’s the chaos that tests the structure, the laughter that makes solemnity bearable—until, of course, he takes it too far. Everyone else, no matter how colorful, ends up orbiting the tension between these two poles.

Supporting Players and Shifting Allegiances

Richard hardly rises to heroic stature. He’s more of a voyeur, chronicling the events without shaping them. He envies Henry, needs him, and ultimately sinks into moral complicity. This isn’t the tragic arc of innocence lost so much as a slow yielding to gravity—a man seduced by composure, drawn like a moth to still flame. Richard doesn’t choose darkness; he allows it to choose for him, and then finds reasons to call that surrender romantic.

Charles, by contrast, resists but only until resistance turns inward. He begins as one half of an inseparable mythic pair, but ends as a ghost of himself: violent, broken, increasingly unmoored. His alcoholism isn’t just escape; it’s erosion. The twin once balanced by Camilla becomes distorted in Henry’s realm, his anger a symptom of guilt without outlet. Unlike Richard, Charles does not internalize Henry’s control with awe; he chafes against it, though too weakly to break free. His violence toward Camilla is less rebellion than despair—a man watching the myth slip out of his hands.

Francis hovers somewhere between this polarization. Dandyish, high-strung, full of biting asides and affectation, he seems immune to the seriousness of it all…until the mask slips. When things fall apart, Francis doesn't rise; he collapses. His beauty, his wealth, his charm - they're not armor but stage props. And when the production ends, he has nothing to stand behind. He lacks the fortitude for real complicity, but he lacks the moral backbone to resist it either. In the end, he’s decorative, an ornament, another victim of an aestheticized life taken too literally.

Each of them illustrates a different response to Henry’s quiet dominion. None can match him, not in will, not in conviction. They follow, even as they flinch. And that’s Tartt’s genius: the intrigue is in what Henry does and just how readily the others let him do it.

Classical Ideals in a Shifting World

Tartt’s novel lingers in the mind because it sets Greek tragedy against the entropy of modern life. The students don’t merely read the ancients; they attempt to live them, hoping to extract some sine qua non kernel of meaning from archaic rites. However, the reality they inhabit belongs to an era that’s unmoored from old certainties. They crave a rooted worldview to brace themselves against post-truth chaos.

I recall a time when I, too, was enthralled by the measured logic of the classics—a tidy harbor in a sea of contradictions. But that security often proves fragile, like a quidnunc chasing rumors of ultimate truth that never quite emerge.

The Birth of Dark Academia

Over the decades, The Secret History has become the ne plus ultra for Dark Academia: old souls who adopt the aesthetic of aged libraries, archaic texts, and flickering lamplight. They reject cozy hygge convenience in pursuit of something more challenging: wool blazers instead of sweatshirts, Latin over apps, a contemplative hush replacing easy chatter. For many, it’s not nostalgia, but a resistance to the softened edges of modern life, and a quiet openness to the low, constant susurrus of deeper meaning. Skeptics see it as a flight from progress or a transitory meme, but adherents find in it a chance to feel connected to an older, more mysterious intellectual/aesthetic tradition.

The Aftermath: Henry’s Onus and Camilla’s Loyalty

Some argue that The Secret History falters after Bunny’s death, as if the novel’s tension dissipates once that climactic moment passes. But I’d argue the opposite. The book grows stranger, heavier more tragic. Henry now shoulders the crushing onus of holding the group together under the weight of consequence and silence. He was made for the theater of the esoteric, not the brutal logistics of aftermath. Without Bunny as the counterbalanced deuteragonist, Henry becomes untethered, like a planet without a sun.

And yet Camilla remains. Not as an accessory, but as a kind of priestess. While Charles spirals and Francis withdraws, she stays beside Henry, not out of naïveté, but conviction. Her loyalty is not romantic so much as sacramental. She doesn’t just love Henry; she witnesses him. She endures the collapse of the myth they both helped build, refusing to disavow it even as it cracks in their hands.

Henry’s final act—a suicide that reverberates—reads less as surrender than ritual. He chooses death not to escape, but to preserve what little remains of the ideal. Like Achilles, he doesn’t flail against his fate; he walks toward it, grim and unwavering. Camilla becomes his Antigone, not seeking justice, but enacting devotion. She doesn’t plead or explain. She remembers.

In a novel full of brilliant men losing control, it’s Camilla who holds the center. She survives not untouched, but unshaken. While the others descend into guilt or denial, Camilla carries Henry’s memory like a relic: not to glorify him, but to ensure he is not forgotten. She is not merely left behind; she chooses to stay.

Tragic Romance in Shadow and Silence

The romance between Henry and Camilla simmers quietly beneath the surface, unspoken for much of the novel, only fully illuminated in its final pages. And yet, it feels inevitable, as if we always knew. They embody a kind of tragic idealism, a doomed love forged not in declarations, but in shared glances and tacit loyalties. Like Pyramus and Thisbe, they damn fate for the fleeting joy of truly knowing one another. Their union exists largely off-stage, which only intensifies its glimmer. We don’t see it unfold; we sense it, slowly, as it crystallizes into something devastatingly palpable.

When Camilla says, "I still love Henry," years after his death; it cuts deeper than any confession made in the flush of youth. It’s not dramatic; it’s resigned. A woman who found her soul’s match and knows she will never again accept a substitute. Her grief is dignified, devastating, unflinching. She becomes not just Henry’s lover, but his mythic mourner: the one who endures. She is a beautifully tragic figure besieged by fate, robbed of her beloved, unwilling to settle for the simulacrum. Her forebearance in the final act is a quiet heroism; a loyalty unscathed by time, and unscathed by the banal.

Who Truly Leads and Who Follows?

In the end, The Secret History confronts us with a realization we often avoid: genuine leadership is rare, and most of us fall into supporting roles even when we believe we’re in charge. Henry isn’t exactly a paragon of virtue, nor is he a one-dimensional monster. He’s a reminder that power can be quiet, seated at the corner of a dimly lit library, orchestrating a collective fate without ever raising its voice. The rest of us, so certain of our autonomy, may wake up to find we’ve been dancing to someone else’s tune all along. That unsettling ripple is Tartt’s greatest triumph: showing us how easily we become minor characters in a story written by a figure as remote and compelling as Henry.

Epilogue

When I finished The Secret History, I couldn’t leave it behind. I found myself slipping into sudden reveries, walking through the quiet corridors of my own thoughts, confronting feelings I hadn’t expected. There was a lingering tension; that between admiration and revulsion, between understanding and unease. Henry loomed largest. Magnanimous, yes. Cold, certainly. I hold him in deep esteem, and yet—he’s a killer. Not a man tormented by guilt, but one who almost seems to thrive in the wake of what’s been done.

And I wonder: would I have felt any different in his place? The exigencies of the day, the necessity and all; how easily those arguments wrap around you like fine silk. That’s the danger, isn’t it? Not the act itself, but how justified it can begin to feel.

These characters mean something to me. They arrived as archetypes: The Charmer, The Stoic, The Beauty, The Twin, this simplicity made them feel mythic, inevitable. We always assume we’re the protagonist. The hero, the dramaturge, the one guiding the plot. But are we? Or are we just fulfilling our role, stepping into the grooves carved by forces older than we understand?

Sometimes I catch myself identifying with Henry. It makes me pause. Is it vanity? Narcissism? Or simply a yearning to believe I possess agency—that I’m not just carried along, but carving something of my own? He has gravity, presence, the ability to shape his world. That’s intoxicating. Terrifying… I want to be. I am. Surely.

There’s also the classical pull stronger than ever. The quiet ache for a time when honor, dignity, reflection were not affectations but lifeblood. The pale glow of a crepuscular past, haloed by ritual and myth, where every act had consequence, and every choice mattered.

There’s beauty in that structure. But there’s also a question I can’t shake: what happens to those of us who crave order in a world that only offers entropy? In the halcyon days of classical yore, were we well and truly ourselves? Is it only now in our own time that fact & fiction bleed into an inexorable mess? Or perhaps this is simply the eternal human condition and nothing’s ever really changed?

These questions, more than any murder or myth, are what stay with me.